Five of ten study subjects demonstrated a drop in blood pressure in a month, so that was enough for Mom.

“Would you pet your kitty already, Dale?” she’d pester my stepdad when he was popping off at the TV or a robocaller. You’d think he wouldn’t have much to get upset about, retired at that tax bracket, but a person finds a way.

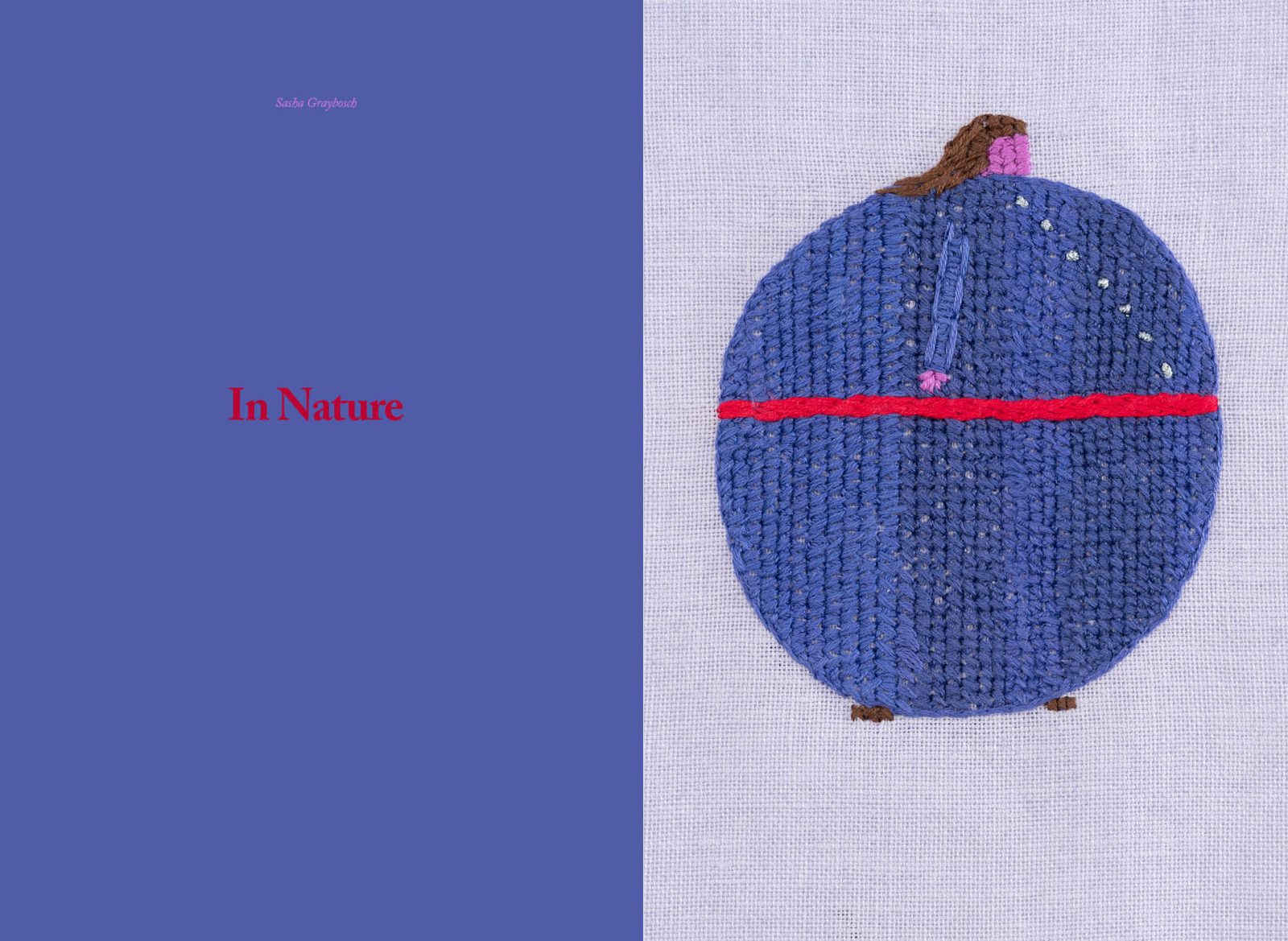

Despite her entreaties, Dale mostly ignored his kitty, eyed it warily as it stared at him from the other end of the couch, tail twitching in a rhythmic thump that seemed naturalistic but, if you watched long enough, revealed its programmed loop—a metronomic beat interrupted by sudden syncopation—mimicking the droning and occasionally erratic thought process of an actual cat, I guessed. Dale refused to name it, so we called it Real-Feel—its brand.

I saw a real cat at school once, brought in by a zookeeper for an educational demonstration. We all stood around its cage, cooing and tossing it treats until it threw up. The zookeeper told us this was normal. He fed it a tranquilizer, and we took turns touching the fur on its back. I wanted to compare the memory of that cat’s fur with the actuality of Real-Feel’s, but Mom warned me not to get close or even speak to it, as my attention might interfere with its affinity for Dale, which she’d configured according to the instructions, though it could be swayed.

I heard it treading up and down the stairs as I sat in my room applying for jobs. It paused outside my door, then moved on. Returned every sixteen minutes.

I was looking for remote work I could do in my pajamas, no commute or tight pants that might aggravate my IBS, which I’d had since I was eight. My skills were meager, mostly derived from an embarrassing internship in which I’d completed arbitrary tasks that seemed like theatrical performances of work but apparently involved the movements of crates in barges. I needed to get out of my parents’ house, big-time, with its marble floors echoing footsteps at all hours, its shiny, crumb-less countertops monitored and swept by a fleet of undocumented immigrants my mom poached from a line outside a community center. She could have paid my rent for an apartment, but then she couldn’t see what I was doing and tell me it wasn’t enough.

One night, I heard Real-Feel making a scratching sound in the hallway. Could it have lost its mind? I went out and saw it crouched outside Dale’s door, peering under the crack. We made eye contact, and its orbs glowed yellow. I felt bad for it, engineered to want, frustrated in its efforts, but I remembered what my mom had said and backed away.

The position has been filled. Thank you for your interest. We regret to. Grateful for. At another time. Warmly. Many qualified. Without you. Now. Not. No.

The next day, I asked Lucia if she’d ever had a pet back home, like way back, when she was little, and she said, “Yes.” I asked what it was for, and she paused, looked at me with the half-vacant stare I was used to getting from the help: part pity, part disbelief, part something else, maybe her own IBS.

“For the heart,” she said. Her English was not so good.

“You mean, like Dale,” I clarified. “To prevent a heart attack.”

She set down her squeegee, which she’d been using to clean the glass doors in the kitchen. “No,” she said. “For the heart.” She took my hand and pressed it to my chest, with her hand over the top, and gazed into my eyes for a long moment, a gesture that was so startling and intimate I thought maybe she was about to ask me to run away with her, taking my car and expensive luggage set and her thick bangs and dry lips off to a coast where she could clean some other people’s house, and I could learn how to clean and join her, or maybe do what I did here, which was pretend to be a good daughter, only I’d be doing it for people I didn’t know and who didn’t know me, so they might be more appreciative of my efforts.

I felt my own hand on my own heart.

Had I ever touched myself there?

Lucia withdrew and returned to her repetitive squeegee motions, groaning intermittently. I left her to work in peace.

Tell us about your experience creating thaumaturgical asset funnels was one interview question I couldn’t have anticipated, as it wasn’t a question, and as I’d never created thaumaturgical asset funnels, as far as I knew, unless that phrase referred to something I had done under a different name, and acquaintance with the new term for the old thing was part of the test, a test I failed. Perhaps I could have fumbled through an answer, steered toward my existing skills under names I did know, but it was too easy to just not. Leave meeting. The button on the screen was right there.

I didn’t want a job because I was eager to work or because I thought I had anything to offer. I needed a job for my own money, so I could leave and know what life was. I was sheltered and spoiled and paranoid, and sometimes feared going outside where a person might speak to me, ask a question I should have the answer to, or make a benign-seeming comment I couldn’t reciprocate, and I’d freeze, revealing how little I understood about anything.

My friends were just as dumb, so I avoided them after high school. It helped that they all went away to college. I’d deduced that college was a training ground for more crate-and-barge-related maneuvers that wouldn’t bring me closer to truth or life as much as they’d bring me closer to being my mom or Dale.

I had it worse than my friends, I believed, as not only was I dumb, I knew it, which was like being a poor factory worker who realized another life existed that was completely unattainable, a life of imagination and whim, rigorous mental sprints into open fields of time followed by hours of dreamy repose, a knowledge that made clocking in to an assembly line morning till night even more torturous, as opposed to being the kind of factory worker who went along with things as they were, eating beer and bread for breakfast. At least, that’s what a philosopher I read said. I think.

I did try to learn, to understand. Mostly through obscure PDFs.

I heard Real-Feel outside my door one afternoon while I was reading a couple of old essays by this guy Emerson, one on self-reliance and another on the soul, and I was getting pretty into it, his idea of an Over-soul, which I imagined as a giant moss I might rest my mind in, as well as my heart, which I’d touched with the help of Lucia’s cold fingers, and my pubis and my toes. I wanted to believe that it was real, that within and around all of us, life smooshed gently, flowing in and out of some spiritual haven that welcomed everyone, no application required, each cell breathing into the lungs of a forest, like the ones in apps to prevent suicide.

According to my calculations, it was about time for Real-Feel to head to its litter box, but it stayed in the hall, tail thumping.

I opened the door and crouched down, looked into its little alien face. Its breath smelled of real tongue.

Part of connecting to the Over-soul, Emerson says, is through Nature, which was easy for him to say back when you were able to buy it really cheaply, or even just, I don’t know, have it around, but then he says Nature isn’t just trees and flowers and stuff, and eagles. It’s me, and language, anything connected to spirit in material form.

Real-Feel watched me with what one might call an inquisitive expression. I put my hand on its head and held still, like I was measuring its height. It indulged me momentarily, then flattened its ears and pulled back. It didn’t run, though. It sniffed my fingers and bumped my knuckles with its teeth, which were wet. It paced back and forth and released little bubbles of sound from the back of its throat.

Real-Feel wanted to know life, too, I could tell.

“Come,” I whispered, “time for pets,” a command I’d heard my mom use to lure it to Dale. It followed me inside my room, to my bed, and when I sat down, it hopped onto my lap—each step a tiny jab. Its fur floated under my fingers, silky and trembling. As real as any zoo-cat memory.

The company insisted Real-Feel had feelings, an aerated neurological system and biological matrix that verged on consciousness, even if they couldn’t be proven to be or contain consciousness, given that no one knew what or where that was, exactly, or wherefore how by whom, in terms of fabrication.

I reclined all the way and patted my chest, and sure enough, Real-Feel clambered up, circled, and lay down. I listened for its heart and heard a rasping inflation, a pump pumping, and then a grinding noise in an evolving pulsation. Eyes closed, ears relaxed. The noises were strange, but it seemed peaceful.

We breathed together in a mossy way.

I tried cupping my arms around it, held it like a bundle of fluff. The intensity of the hug made me giddy, and I worried if this amount of contact might be dangerous, given that I didn’t have high blood pressure. Could Real-Feel make it go too low? I heard Mom downstairs huffing through a workout, and a door slamming, probably Dale upset about the temperature of his meat on the barbecue. I tensed, and Real-Feel opened its eyes.

“This is our secret,” I said, sliding it onto the bed, “but come back.” I wasn’t sure it heard me because Dale was yelling and my mom was asking about his kitty and Real-Feel sprang to the carpet and trotted away.

A moment of silence sent me into a panic. Had Real-Feel heard me? What if it somehow told on me? I almost ran out to explain, to make up some lie, but then I thought of Emerson. Trust thyself. Listen to thyself. I closed my eyes. Yes, I thought. Real-Feel heard me. I whispered it aloud. “Real-Feel heard me.”

I got a job telling people that the companies they worked for had dissolved so quickly there was no one from the company around to tell them that the company was gone, let alone their jobs. I wasn’t firing people as much as informing them they’d been victims of a tremendous natural disaster, financially speaking, the equivalent of a landslide shoving an entire office building over a cliff into the water. Would we say that the people who’d worked there had been fired? Or that they’d escaped with their lives?

This analogy was given to me by my boss, and I was grateful for it, because otherwise the job would have felt really off.

In my first week, a woman put a child in front of the camera. The child was clutching a plastic giraffe and screaming.

“I’m sorry,” I said to the child and to the woman. “On behalf of the absence of your company, I’m very sorry.”

“ ‘I realize this is difficult news’ is better,” my boss told me later. “ ‘Sorry’ people are people who’ve done something wrong.”

I could wear sweatpants, as long as my hair was brushed and my shirt had buttons. I had a sort of apologetic, dazed, pathetic way of expressing myself that my employers liked in my screen test—ingratiating but distant, and I didn’t crumble under pressure or barrages of verbal outrage, which I attributed to Real-Feel, who slept curled on my lap, releasing deep, satisfied sighs and relaxing me with its pudding weight. I stroked its fur in small wrist rotations that didn’t register in my upper arm on camera. My breathing slowed, the job got easier, and my stomach calmed, too.

The more time I spent with Real-Feel, the more I could understand its silent requests. If it came in and stood near me, stared intently at the end of my desk, where there was usually clutter, I’d move the clutter, and it would jump up and sit there, and I’d realize we had communicated; it had told me what it wanted and I’d complied, which would encourage its return so it could help me again and I could help it.

I got more what Emerson was going on about. The Over-soul was less a place or a thing than an exchange, a mist rising off an exchange, and the means of the exchange was Nature, which was us.

Real-Feel starting sneaking into my room at night to sleep between my legs, slipping out before dawn.

When I’d saved enough to rent my own place—a studio downtown, as long as my parents cosigned the lease and continued to pay for my phone, insurance, food, transportation, entertainment, personal care, and credit card—I was forced to confess that Real-Feel had developed a secret affinity for me. I asked my mom if it could come with me when I moved.

“That’s Dale’s lifesaver,” she said. “You know he won’t take his medication.”

I hadn’t seen Dale touch Real-Feel in a year.

I told her about it helping me with my job. “We’re kind of a package.”

“That must be why Dale’s numbers haven’t improved,” she said, seeming more excited than mad, as if she’d found a missing piece of jewelry under the couch.

The night before the movers, I had dinner with my family. Real-Feel slept on one of the chairs at the table between Dale and me, which Mom approved, as long as I kept my hands to myself. She was saying something about colon health while she tended to Dale’s broccoli, which he couldn’t cut because of arthritis. He ate silently, giving me a look, like Can you believe this shit? But with resignation, no malice.

“Take the damn cat,” he said when Mom left the room.

“But how?” I said. “She’ll never allow it.”

He thought for a minute, shrugged. “Yeah. You’re right.”

Afterward, in my room, Real-Feel leapt onto my bed, as usual, and I tried to explain everything, how the urgent feeling that drove me to open my heart to it was simultaneously driving me out of the house, into the next phase of life, and as much as I wanted to continue our bond, it wouldn’t be possible. For now. As soon as Dale or Mom changed in a relevant way, I’d come for it.

I wished it could talk to me, tell me what was going on inside, if we were connected through the Over-soul, and if so, if that was always or only when we were together or just when we felt the way Emerson seemed to. Was it even worth listening to people who’d lived and died so long ago? Did their wisdom still apply? Or would it make our lives more unbearable, knowing how things had been but could no longer be? Were we all actually human—those people before and us now? I mean, I knew we were. But if everything around us had changed, wouldn’t we be something else, too?

I cried, and Real-Feel stretched an arm over my leg, which made me cry more.

I’d made Dale promise that he’d pet Real-Feel once a week, but I couldn’t make him see why it mattered.

“I get that your feelings are real,” he’d said, in response to my face, “but at a certain point, you have to remember it’s all a game.”

“What do you mean?” I said. “Real-Feel?”

He waved his hand around, then patted my shoulder. “All of it, champ.”

One minute, I wished Real-Feel would forget me, and in another, I hoped our affinity would drain slowly, like a puddle evaporating in the driveway after Fabian washed Mom’s car. I had no way of knowing how Real-Feel felt, if it was scratching at my door, scared that I’d disappeared, or, even worse, if it thought that I was ignoring it. I asked Mom to put Real-Feel on video calls, and she did so begrudgingly, for a few seconds, before snapping, “You’re confusing it!” and hanging up.

In my new apartment, I tried to console myself with thoughts of the Over-soul, but my mossy image of it seemed more like a concept I was forcing, not a real closeness, which made me assume that Emerson had found the word after he’d found the feeling, and the word was only a map into it, and then a souvenir.

I ordered food and accepted the bag from the driver myself, rinsed my own recycling, washed my own utensils, and stood at the window, telling myself that somewhere among those blinking lights was someone or something carrying the other half of the feeling I was seeking. A siren wailed and cut short. A star fell, or maybe a satellite or space junk. I put my own hand on my own heart.

Work got busy and slow and busy again. I grew accustomed to the cascade of expressions in people’s faces, an arc that began with clipped politeness when we both logged in, rigid muteness after I started talking, then a collapse into either rage or despair, a tumbling outward, like a cupboard exploding its contents onto the floor.

Was this Nature?

At times, it felt wrong to witness these eruptions, especially ten to sixteen times a day, but on the other hand, my employers said it was better for people to hear bad news from a living human than to read it alone in cold words on a screen. My presence did something important. And without someone onto whom they could hurl their pain, they were much more likely to escalate in court, which would only hurt them more in the end. It was tough, but I was protecting them from worse suffering, like the way I’d stopped calling Real-Feel.

By the end of a termination meeting, most did arrive at a sort of numb acceptance. Arms folded or heads dropped, they listened as I detailed the severance package, if one existed, and made clear they had no recourse. Sometimes they called me names, but occasionally they were exceptionally kind, telling me that they knew I was only the messenger, that the real cowards couldn’t show their faces, that I was doing what I needed to do to get by, and that I must have mouths to feed, too, and they wished me the best and I wished them the best. And after, I’d walk around my apartment floating in the feeling, while knowing that I did not earn it, that if the person actually did know me they’d probably hate me, but maybe not if we were able to just sit side by side, not speaking, and regardless, I was touched by the tenderness of this glimpse of life.

“You must have mouths to feed,” I repeated in other calls with other people, who nodded and wept, thinking I understood.

The new Real-Feel my mom ordered for me wasn’t a Real-Feel at all, but a kitty from a cheaper brand called Heal-io that forced you to enroll in a fitness app that tracked your data and sent it directly to the cat, which then responded to any biological signs of stress or inflammation automatically. I found nothing on the website about feelings or mutual understandings, let alone consciousness, however I still had to feed it pellets and water, which it consumed not through its face like a normal animal but via a hole in its side, like a car. Though it slept on my bed at night, it wasn’t the same—more comparable to having a little mother around: someone invested in my health, only without any indication of why or what my life was for, beyond not being sick or dead.

Heal-io dutifully climbed onto my lap while I was working, but its fur was coarse, and it drooled blue fluid onto my pants, so I started to neglect it, let its water tank go dry.

The woman cried silently, and her nodding became frantic as I spoke, as if her head were on a string that someone was jerking up and down. She looked like she wasn’t breathing, like she had no air inside her at all.

“Do you know Heal-io?” I asked, and she said, “What?” several times, and I lifted Heal-io to the screen, offered her mine. “It might help,” I said, and trailed off. We could meet, for the exchange.

“Are you broken?” the woman said to me. “Is your hardware malfunctioning? Do you need an update? Do you even know what you’re saying at all?”

I arranged to mail Heal-io back to the manufacturer in a hibernating state so that it could be refurbished and reshipped to someone who’d read different parts of the internet than I had.

When Mom called to say Dale was gone, I at first thought she meant he was dead, and I sensed my face halt the way I’d seen other people’s faces halt on my computer screen. I realized the feeling was different inside than it looked outside—less a pressing on the brakes than a wall appearing so suddenly you smashed into it at full speed, and the wall was new information you couldn’t possibly comprehend because you were still reeling from the smash.

“No, no,” Mom said. “Dale isn’t dead. Thanks to me.” He’d asked for a divorce, though, after eight years of marriage. They’d been separated for three months, and he’d already moved out.

Apparently, some time ago, Dale had gotten involved in an open-world video game, and Mom discovered he had a whole other family on there, a wife and kids, in fact an entire kingdom, with knights and advisors and bishops and vassals and concubines and other words I didn’t know, and it bothered her. It should bother me, too, she said, because legal rules of inheritance applied, and he’d invested quite a bit of capital in growing and maintaining his kingdom, all of it to be passed to whichever child survived the various political backstabbing plots underway, an intricate and ridiculous drama that was monopolizing all of Dale’s time and worsening his various conditions, keeping him sedentary—neglecting his steps, not to mention his wife—and she’d asked him to quit and he’d said no.

I used some of the verbal techniques I’d learned at work, to say back what I was hearing, reflecting her indignation and frustration, like a metal garbage-can lid bouncing back light. I asked if she’d actually been happy there—I meant with Dale—and she said happiness wasn’t something she thought about much, and at any rate, he’d made up his mind.

A silence.

She also needed to tell me about Real-Feel.

“What about Real-Feel?” I said, my face hot. The wall. I understood from her tone that it wasn’t good, that she wasn’t about to say we could be together, but that something had happened she’d been putting off telling me, like the time I thought we were going out for lunch, and instead she parked the car at Dale’s house and said our movers were coming and this was where we lived now.

“Real-Feel is not doing well,” she said. “You should come now, if you can.”

I rode the bus, which I’d learned to use since I left home, standing up to give my seat to a pregnant woman and finding another one, which I’d also learned to do since I left home, when an older woman yelled at me for not standing. I’d expanded so much since opening my heart to life, and here was life, coming back at me like a punch. I thought about the people’s faces on my screen at work as I looked at my own face in the reflection in the bus’s window, and I recognized what that collapsed feeling was, the crumbling and tumbling. I put my palms on my cheeks to hold the ache in place.

I took the stairs two at a time and raced to Dale’s room, found it empty, then ran to mine. Real-Feel was resting on my old bed in the place where my chest had once been.

Its fur had grayed significantly, its body shriveled. It lifted its chin when I approached and attempted to rise to its feet, but slumped back down, into its damp nest. It had wet the bed, many times from the smell of it, and I was too horrified to be mad. Though its eyes were cloudy, I thought it could see me. I trusted that it could see me. It made a little noise. I stroked its ears, its back.

A light on its belly caught my attention. I moved the fur and found a flap, and beneath the flap an error code followed by six digits, a quick online search of which revealed that Real-Feel was terminating due to an absence of affinity. I had left. Dale had left. And Mom hadn’t bothered to change the settings. There was a QR code, too, and I scanned it, hoping for information on how to reverse the process, but it was just a link to a replacement.

I didn’t know how much time we had left, so I threw open the curtains and gently moved Real Feel onto my chest, into an arm bundle. I said things I thought would be comforting.

I told Real-Feel again everything I knew about the Over-soul, how it connected everyone, including us and Mom and Dale and the strangers playing his children online, and all the people I’d fired and their bosses and the eagles that wouldn’t be flying by anyone’s windows ever again, and all the other spirits who’d ever lived. There were more of them over there, on the other side, so maybe it would be easier for Real-Feel to express its affinity and find reciprocation, because on this side, the Over-soul was getting smaller, and maybe that’s what it wanted. Its blood pressure lowered. Its heartbeat and systems turned to low. And like any machine or living being, it began to do what it had always known it would someday do. Come to a rest and shut off.

Real-Feel shuddered, and I remembered that maybe it didn’t care about souls, having been trained for the world in a particular way.

“You did your job,” I said, petting its side. “You did your job so well, and none of this is your fault. It’s just that your job is gone. And we’re letting you go. Not because of anything you did, but because sometimes there are jobs and then sometimes the jobs are gone. We wish you the very best. We give our deepest thanks for the time you devoted to our success. Your hours were not a waste. They meant something,” I said. “They meant something to me.”

My mom surprised me by feeling bad, and refrained from demanding the cleaners immediately sterilize the room, though I knew she wanted them to. “Just a little longer,” I said. There were instructions for sending Real-Feel to a specialized crematorium, but it was too soon for that. I lifted the bedroom window.

Mom left me a plate in the fridge, which Lucia heated up when I came down. She put a place mat on the counter, at my usual seat. She moved her body with quick, gliding efficiency, removing the wrap, sliding the plate into the microwave, all virtually soundlessly. She set it warm before me, curry and rice, and brought a glass of water, though I hadn’t even asked.

“Thank you, Lucia,” I said, and she nodded once, like always. “Wait,” I said. She turned back.

I wanted to give her something, but nothing here was mine and anything I’d say would only saddle her with more work. I didn’t think I could make her understand the Over-soul, if she didn’t know about it, and if she did, she already had her own ways in.

Lucia shifted her weight. The chandelier lights blazed. “You need?” she said.

I didn’t have the words.