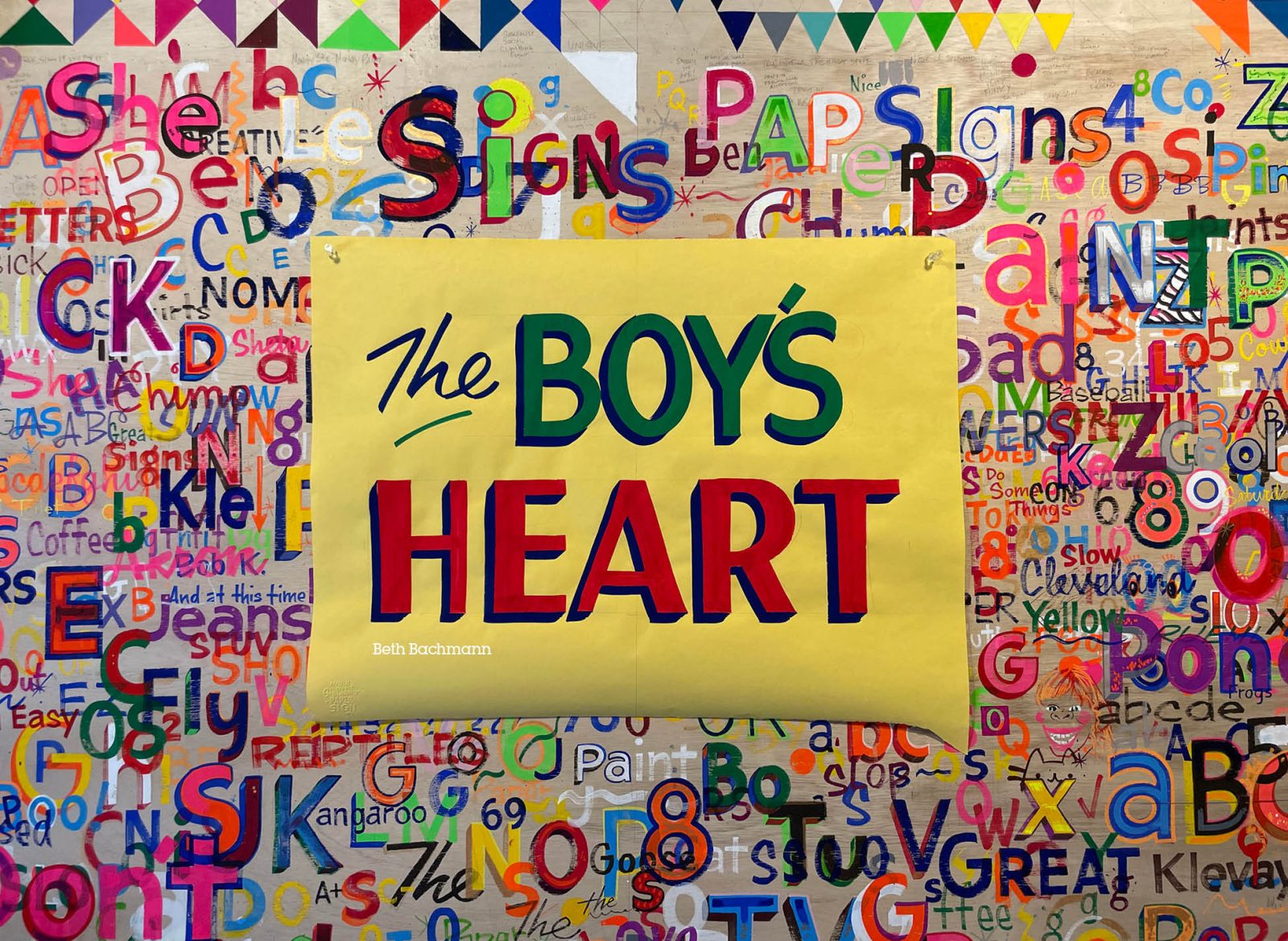

“The Boys’ Heart” was awarded first prize in the 2023 Zoetrope: All-Story Short Fiction Competition, as judged by Jamil Jan Kochai.

There is only one way to know if the egg on the ground is a bird or a snake, so the boy picks it up and places it in his chest pocket. Birds can fly, but snakes can swim, which is terrifying. He studied a bird wing once while the horse ate and then went home and bandaged one of each of his dolls’ arms and his own arm until he needed it to make a paper airplane. He never wanted to be a doctor; he doesn’t like getting dirty. In the bath, with his arms behind his head, he thinks of the picture he saw of an execution, sinks his head underwater, and wonders how many nests birds have made using lost strands of his hair. When they told him his friend’s heart had a murmur, he thought of the starlings taking the shape of a snake taking the shape of the sea. When his friend said a murmur meant a hole in his heart, he thought of his pet rock’s pet stone in his pocket that got away. His friend says that after the surgery, he can’t jump for a month. How do the birds do it—trust that something invisible will carry them? A snake can hide in the grass but leaves a trail to its home. What he knows most about a snake has to do with its jaw, and with a jaw like that, why can’t it sing like a bird? Kissing seems hard to do with your hands behind your back, as though you are bobbing for apples. Snakes have an organ in their throat that opens and closes like a heart, but it controls the flow of air instead of blood. Still, it has to do with breathing, and when the boy listened to his friend’s heart, he heard it hissing. Some birds can sing rising and falling notes simultaneously. He will make the thing in his pocket a bed.

The mechanism of a music box is teeth. The boy’s lips press against wax paper like the flowers he crushes in his mother’s books every hundred pages. He likes to look at leaves under his microscope, especially the cells below the epidermis that want to be as close to the light as possible while remaining protected, and further down below them, the stomata, small holes that expand and contract to let air in. The first high-resolution photos of the sun show cells, not hexagonal like a honeycomb, but nevertheless buzzing with activity. Humming against the wax-paper comb, the boy is a bee.

Before he begins to dissect the flower, the boy looks at the flower. He uses his scalpel to cut down the length of its hollow body to search for eggs. The best flowers to anatomize are lilies and tulips; roses and irises are too complex for a beginner. The boy’s friend gives him a box folded out of blue paper. He can use it, he says, for his flowers. The boy keeps the egg warm by breathing. One way a mother is like a predator is patience. His mother pauses her attempt to perfect Starry Night in nail art—“It’s always the pinkie that goes awry,” she says. “Look at your hands: you got your fingerprints pressing your hands against the wall of the womb.”